The Rabbit Gastrointestinal Tract

Introduction

The Rabbit Gastrointestinal Tract is a structure of remarkable precision. It has evolved not for convenience, but for survival—designed to extract maximum nutrition from a diet most animals would starve on: low-energy, high-fibre forage. Every part of the system is geared towards movement, fermentation, and efficiency.

But what evolution refined for wild resilience is, in the domestic setting, surprisingly fragile.

Even small disruptions—stress, dehydration, lack of fibre, a sudden change in diet—can tip the balance. And when that happens, things don’t just slow down. They stop.

This is gastrointestinal stasis, and it is one of the most common and life-threatening emergencies in rabbit care. It doesn’t announce itself with blood or noise. It begins quietly—missed meals, fewer droppings, lethargy. And if not acted on swiftly, it can spiral into a fatal shutdown of the gut.

This article provides a practical, anatomy-informed overview of how the rabbit gut functions—from the unique fermenting power of the caecum to the vital (and often misunderstood) role of cecotrophy. You’ll learn how fibre fuels this system, how movement keeps it working, and how stress, pain, or poor diet can send it into dysfunction.

It’s not written for those looking for shortcuts.

It’s for those who understand that rabbits are not “just small herbivores,” but highly specialised animals whose entire health is built on the uninterrupted motion of their gut.

Understanding these principles isn’t academic.

It’s not theory. It’s care.

And often, it’s the quiet difference between thriving—and dying unseen.

Precision in Motion

The rabbit’s digestive system is a study in efficiency and fragility. As strict herbivores, rabbits have evolved to survive on low-energy, high-fibre diets, extracting nutrition through a finely balanced combination of mechanical sorting and microbial fermentation. Their survival depends on near-constant gut motion. When this system falters, consequences follow quickly — often fatally.

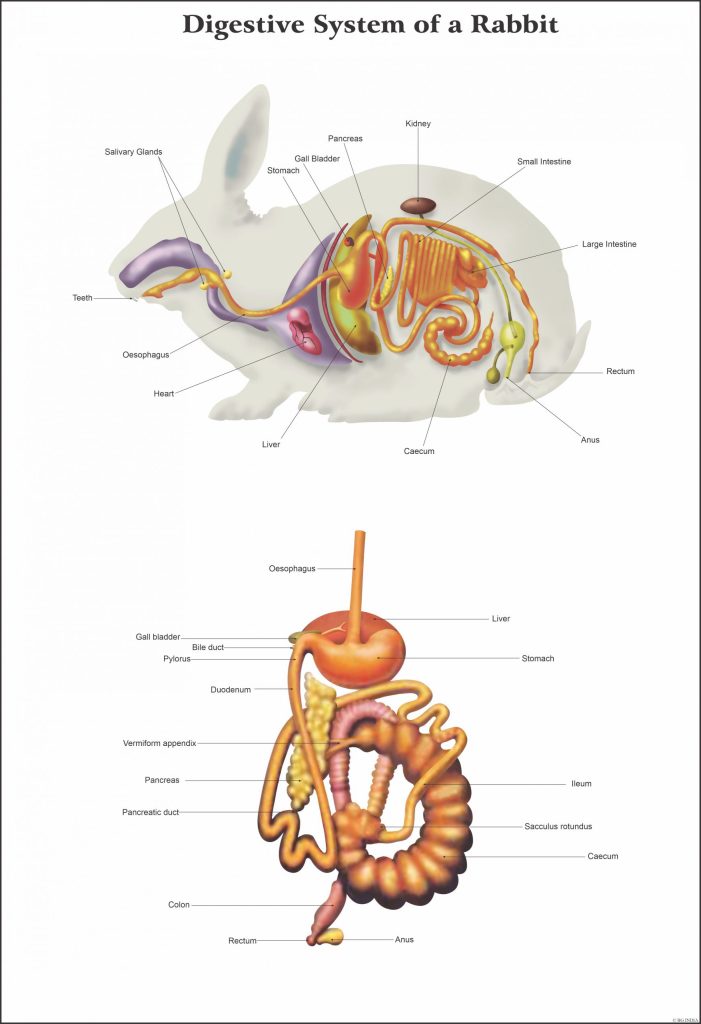

Food enters the mouth, where the rabbit’s incisors slice and molars grind it into manageable particles. From there, it passes down the oesophagus into the stomach — a highly acidic environment that remains active even between meals, sterilising incoming material and beginning protein breakdown. The rabbit stomach is rarely empty in health; continuous grazing ensures a steady supply of food and stimulates downstream motility.

In the small intestine, enzymatic digestion extracts simple nutrients — sugars, amino acids, fats — which are absorbed directly into the bloodstream. Yet much of the plant material, particularly structural fibres like cellulose, passes through unchanged. It is not here that rabbits unlock the full value of their food.

At the junction of the small and large intestine lies the caecum: a vast fermentation chamber where microbial symbionts do the work that the rabbit’s own enzymes cannot. In the caecum, digestible fibres are broken down into volatile fatty acids, amino acids, and essential vitamins. This microbial processing is not a minor supplement — it is vital. Without it, the rabbit could not survive on forage alone.

Meanwhile, the colon — far from being a simple waste conduit — acts as a sorting mechanism. Coarse, indigestible fibres are rapidly expelled as dry faecal pellets, maintaining gut motility. Finer particles and fluids are retained and diverted back into the caecum for fermentation.

The final step in this cycle is cecotrophy: the reingestion of specialised, nutrient-rich soft pellets called cecotrophs. Rabbits consume these directly from the anus, recovering critical nutrients produced by microbial fermentation. Without cecotrophy, essential vitamins, amino acids, and fatty acids would be lost — and the rabbit’s carefully calibrated digestive strategy would fail.

Every aspect of the rabbit gastrointestinal tract is built on this principle:

- Rapid elimination of indigestible material to keep the gut moving.

- Selective fermentation of digestible material to extract additional nutrition.

- Continuous ingestion to maintain both processes without interruption.

It is a system that functions with elegant precision — but one that leaves little margin for error. Disruption of gut motility, microbial balance, or fluid dynamics can trigger a rapid decline, leading first to gastrointestinal stasis and, if untreated, to systemic collapse.

Understanding this dynamic is essential for anyone responsible for the care of rabbits. The gut is not merely a digestive organ — it is the rabbit’s primary engine of survival.

The Role of Fibre in Rabbit Gastrointestinal Health

Fibre is not simply a dietary requirement for rabbits. It is the driving force behind their entire digestive system, shaping both gut motility and microbial balance.

In practical terms, there are two critical types of fibre in the rabbit diet, each with a distinct role:

Indigestible Fibre

This consists of large, coarse plant material — primarily cellulose — that neither the rabbit’s enzymes nor its gut flora can break down. Its role is mechanical. Indigestible fibre stretches the intestinal walls, stimulating peristalsis and promoting the continuous movement of ingesta through the gastrointestinal tract. Without it, gut motility slows, intestinal contents dry out, and the risk of stasis sharply increases. Indigestible fibre is rapidly eliminated as the familiar dry, round faecal pellets.

Digestible Fibre

These finer plant particles — such as hemicellulose and pectin — are selectively retained and diverted into the caecum. Here, microbial fermentation converts them into volatile fatty acids, amino acids, and vitamins. Digestible fibre forms the foundation of the rabbit’s secondary digestive strategy: fermentation and cecotrophy.

Both types of fibre are essential, but it is the balance between them that defines digestive health.

- Without enough indigestible fibre, mechanical gut stimulation fails.

- Without enough digestible fibre, caecal fermentation and nutrient recovery falter.

A rabbit’s diet must prioritise abundant, physically coarse indigestible fibre — primarily through unrestricted access to good quality grass hay — while naturally incorporating sufficient digestible fibre from green leafy plants.

Commercial pellet feeds, even those marketed as “high-fibre,” rarely replicate the necessary particle size, structure, or water content provided by natural forage. Fibre is not just a chemical entity; its physical form is critical to its function.

In a healthy rabbit, fibre is not an optional extra. It is the architecture of survival.

The Importance of Cecotrophy

Cecotrophy is not a behavioural quirk. It is an essential biological process without which the rabbit’s digestive strategy would fail.

After fermentation in the caecum, rabbits produce cecotrophs — soft, nutrient-rich pellets coated in mucus. These are not waste products. They are carefully packaged sources of volatile fatty acids, amino acids, B vitamins, and beneficial microbial proteins, created through microbial digestion.

Rabbits consume cecotrophs directly from the anus, usually during periods of rest. The mucous coating protects their contents from the stomach’s acidity during reingestion, allowing the nutrients to pass intact into the small intestine for absorption.

Without cecotrophy, rabbits would lose access to a major proportion of the nutrition their food offers. Their system is built on two passes through the gut:

- The first to sort, ferment, and concentrate nutrients.

- The second to absorb the products of fermentation.

Failure of cecotrophy — whether through illness, obesity (restricting access), dental problems, or dietary mismanagement — rapidly leads to malnutrition, microbial imbalance, and further gut dysfunction.

Owners noticing uneaten cecotrophs, smeared soft droppings, or an unusual smell around the rabbit’s living area should not dismiss these as hygiene issues. They are early warning signs that the digestive cycle is breaking down — often due to an excess of carbohydrate in the diet or an emerging systemic problem.

Cecotrophy is fundamental.

Without it, the rabbit’s economy of survival collapses.

Factors That Disrupt Gastrointestinal Motility

The rabbit gastrointestinal tract is built for constant, rhythmic motion. When that motion slows, the system quickly destabilises. Several key factors are known to impair gut motility, either directly or through cascading effects:

Inappropriate Diet

A diet lacking in coarse, indigestible fibre is the most common cause of gastrointestinal slowdown. Without the mechanical stimulation provided by fibrous material, peristalsis weakens. At the same time, excess carbohydrates — from pellets, cereals, or sugary treats — alter caecal fermentation patterns, encouraging the growth of gas-producing and toxin-producing bacteria. The combination creates a perfect environment for stasis to develop.

Dehydration

Water is essential for maintaining the fluidity and mass of gut contents. When rabbits become dehydrated — whether through reduced water intake, systemic illness, or environmental stress — intestinal material dries and compacts. This significantly increases the resistance to movement along the gut, further slowing motility.

Pain and Systemic Illness

Pain is a potent inhibitor of feeding behaviour. Dental disease, urinary tract disorders, arthritis, and internal organ disease can all lead to reduced appetite. Even mild reductions in feeding frequency diminish gut stimulation, setting the stage for hypomotility. In addition, certain systemic illnesses directly affect autonomic gut regulation, compounding the risk.

Stress

Psychological stress activates sympathetic nervous system responses that naturally suppress gastrointestinal activity. Transport, unfamiliar environments, loud noises, social disruption, or fear of predators can each act as stressors. In rabbits already marginally coping — through diet or health issues — stress can tip the balance sharply towards stasis.

Medication and Microbial Disruption

The rabbit’s caecal flora is highly sensitive. Administration of inappropriate antibiotics, particularly those targeting Gram-positive organisms, can destroy beneficial bacterial populations and allow pathogenic species to dominate. This microbial imbalance often triggers gas accumulation, toxin release, and further motility failure.

How Gastric Stasis Develops

Gastric stasis does not strike without warning. It is the inevitable result of disrupted gut function — a cascade set in motion when motility slows, hydration falters, and microbial balance shifts.

The earliest stage is often subtle: reduced intake of fibrous foods, mild dehydration, or a minor slowing of peristalsis. With less material moving through the gut, ingesta begins to linger, particularly in the stomach and caecum. As the gut walls continue to reabsorb water from the static mass, the contents dry and compact.

Within the stomach, this drying process transforms the normal semi-fluid contents into a firm, doughy mass. Hair, which rabbits continually ingest during grooming, becomes entangled within this material. In time, what was once a soft food bolus hardens into a dense, fibrous mass. It is often mistakenly referred to as a “hairball,” but in reality, hair is only part of the picture. The primary cause is not the hair — it is the failure of gut motility that allows hair and food material to accumulate unchecked.

Meanwhile, fermentation within the caecum becomes abnormal. With fibre intake reduced and gut transit slowed, pathogenic bacteria gain advantage. Gas production increases, toxins may be released, and the caecal environment becomes hostile. The rabbit, sensing discomfort, eats less — further aggravating dehydration and gut inactivity.

As stasis deepens, the stomach may become grossly enlarged with dehydrated ingesta and trapped gas. Pain and discomfort lead to behavioural changes: a hunched posture, teeth grinding, lethargy. Faecal output diminishes, often becoming smaller, harder, or stopping altogether.

Without intervention, this cycle accelerates. Dehydration worsens. Toxins absorbed from the gut begin to strain the liver and kidneys. If anorexia persists, hepatic lipidosis (fatty liver disease) may develop — a life-threatening condition in itself. The rabbit weakens, slips into systemic shock, and without prompt and aggressive treatment, death follows.

Gastric stasis is not a single event. It is a progression — a chain of small failures that, left unchecked, lead to catastrophic collapse.

the Early Signs of Gastric Stasis

Early recognition of gastric stasis can mean the difference between a manageable crisis and a fatal outcome. Yet the initial signs are often subtle — easily overlooked by the untrained eye. Rabbits, as prey animals, instinctively mask weakness until collapse is imminent. Vigilance is essential.

Reduced Appetite

The earliest and most consistent sign is a reduction in food intake. A rabbit may become selective, favouring softer foods over hay, or may show general disinterest in eating. Even a mild decrease in hay consumption should raise concern. Complete anorexia — refusal of all food, including favoured treats — is an emergency.

Diminished Faecal Output

Healthy rabbits produce a steady supply of firm, round, dry faecal pellets. As gut motility slows, droppings become fewer, smaller, and harder. Strings of faecal pellets linked by hair may appear, reflecting slowed movement and retained ingesta. Complete cessation of faecal production indicates a significant and worsening problem.

Postural and Behavioural Changes

Rabbits in discomfort often adopt a hunched posture, sitting with a rounded back and reduced movement. They may grind their teeth audibly — a sign of pain distinct from the soft tooth purring of contentment. Lethargy deepens as dehydration and systemic distress increase.

Abdominal Changes

In the early stages of stasis, the abdomen may feel unusually doughy or firm on palpation. Gas accumulation in later stages can cause visible bloating. A distended, tense abdomen combined with signs of pain demands immediate veterinary attention.

Changes in Caecotrophy

Disruption of normal cecotrophy is an early clue to underlying gut dysfunction. Uneaten or malformed cecotrophs, a strong smell, or soiling around the hindquarters should never be dismissed as trivial.

Gastric Stasis vs Gastrointestinal Obstruction: Critical Distinctions

Although gastric stasis and gastrointestinal obstruction share overlapping clinical signs, the underlying processes — and the required responses — are fundamentally different. Distinguishing between them is critical to effective treatment.

Gastric Stasis (Ileus)

Gastric stasis is a functional slowdown of the digestive tract, usually developing gradually over hours or days. Reduced intake of fibre, dehydration, pain, stress, or systemic illness weakens peristalsis. As movement slows, ingesta dehydrates and compacts, further impeding transit.

Clinical signs typically evolve over time:

- Gradual reduction in appetite.

- Progressive diminution of faecal output.

- Development of a doughy or firm abdominal mass.

- Lethargy deepening as dehydration and malnutrition worsen.

In early stages, rabbits may still appear relatively bright despite reduced eating. As stasis progresses, systemic deterioration accelerates.

Medical management — including aggressive rehydration, analgesia, nutritional support, and correction of underlying causes — can often reverse stasis if initiated promptly.

Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Obstruction is a mechanical blockage — a physical barrier preventing the passage of ingesta. Common causes include compacted hair and food masses (“trichobezoars”), ingested foreign bodies, or fibrous impactions at natural anatomical choke points, such as the pylorus or ileocaecal junction.

Obstruction differs from stasis in its speed and severity:

- Sudden onset: A rabbit eating and active one moment may become anorexic, bloated, and distressed within hours.

- Rapid abdominal distension: Gas and fluid accumulate proximally to the blockage.

- Acute pain: Marked discomfort, reluctance to move, tooth grinding, or collapse.

- Absence of faeces: Complete cessation, not simply reduction.

- Shock signs: Hypothermia, pallor, weakness, bradycardia or tachycardia.

Without immediate intervention, obstruction rapidly leads to gastric rupture, profound endotoxaemia, and death.

Radiographic imaging is often required to differentiate between stasis and obstruction. In obstruction, the stomach and proximal intestines may appear grossly dilated with gas and fluid, while distal sections are empty. In stasis, the entire tract may be sluggish but not obstructed at a single point.

Critically, treatments that stimulate gut motility — such as prokinetic drugs or assisted feeding — are contraindicated if obstruction is suspected. Attempting to force material through a true blockage risks rupture.

In summary:

- Gastric stasis is a gradual failure of motility, treatable with aggressive medical management.

- Gastrointestinal obstruction is a surgical emergency requiring rapid diagnosis and intervention.

The distinction is not academic. It is life-saving.

The Importance of Rapid Intervention

In cases of gastrointestinal compromise, time is not a luxury rabbits can afford. The longer gut motility remains impaired, the greater the risk of irreversible systemic failure.

In gastric stasis, every hour of reduced intake and slowed transit compounds dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, microbial dysbiosis, and toxin accumulation. Prolonged anorexia — even beyond 12–24 hours — significantly increases the risk of hepatic lipidosis, a metabolic collapse that is often fatal despite aggressive treatment.

In gastrointestinal obstruction, the urgency is even greater. Complete mechanical blockage triggers rapid gastric distension, vascular compromise, endotoxaemia, and shock. Without immediate intervention, rabbits can deteriorate and die within hours.

The key to survival is early, decisive action:

- At the first signs of reduced appetite or faecal output, intervention must begin — hydration, pain relief, veterinary assessment.

- If obstruction is suspected, imaging and, if necessary, surgical exploration must not be delayed.

- Under no circumstances should a “wait and see” approach be adopted in a rabbit showing signs of gut dysfunction.

Owners and veterinary teams alike must treat any significant change in feeding behaviour or faecal output as a clinical emergency until proven otherwise.

Rabbits cannot recover gut motility through rest or self-correction. Without support — often intensive support — the trajectory is predictable: progressive gut shutdown, systemic collapse, and death.

Rapid intervention is not just best practice.

It is the line between recovery and fatality.

Closing Note

The rabbit gastrointestinal tract is not a passive system.

It demands constant motion, constant fibre, and constant respect.

When managed properly, it allows these animals to thrive on forage most species could never survive upon.

When neglected — even briefly — it can fail with devastating speed.

Informed, attentive management is the rabbit keeper’s greatest tool.

Intervention must be swift, but prevention is better still.

There is a hard truth known to those who work closely with rabbits:

- Catch stasis on day one, and you may resolve it in a day.

- Catch it on day two, and it may take a week to mend.

- Catch it on day three, and the chance of survival is remote.

When in doubt, act early.

Rabbits seldom offer second chances.

References

- Harcourt-Brown, F. (2002). Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Meredith, A., & Lord, B. (2014). BSAVA Manual of Rabbit Medicine. British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- Halls, K. E., & Phillips, C. J. (2001). Effects of diet on cecotrophy in rabbits. Physiology & Behavior, 74(3), 327–334.

- Jenkins, J. R. (1999). Gastrointestinal diseases of rabbits. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 2(2), 299–312.

- Coudert, P., Lebas, F., Rouvier, R., & de Rochambeau, H. (1992). The Rabbit: Husbandry, Health and Production. FAO Animal Production and Health Series.

- Halls, K. E. (2001). Cecal motility and the effects of diet on gastrointestinal transit in rabbits. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 85(3-4), 95–102.

- House Rabbit Society (HRS). Educational resources on gastrointestinal stasis and rabbit health. (www.rabbit.org)

Copyright © Redbeck Rabbit Boarding. This article is free to share with credit. No part may be copied, edited, or republished without permission.