Understanding the Rabbit Skeleton

Understanding the Rabbit Skeleton

The rabbit skeleton is a structure of extraordinary design, built for speed, agility, and survival in the wild.

But in the domestic setting, this same design becomes a source of fragility and risk.

A rabbit’s bones are light, delicate, and highly specialised for short bursts of explosive movement, not for rough handling, vertical jumps, or sudden restraint.

Understanding how the rabbit skeleton is built — and how easily it can be damaged, is essential for responsible ownership.

Handling techniques, housing design, and daily care must all respect the limits of this remarkable but vulnerable system.

This article provides a practical overview of rabbit skeletal anatomy, common injuries, and how to protect these animals from accidents that can, quite literally, break them.

Knowledge is not just academic.

It is the foundation of safer, more compassionate care.

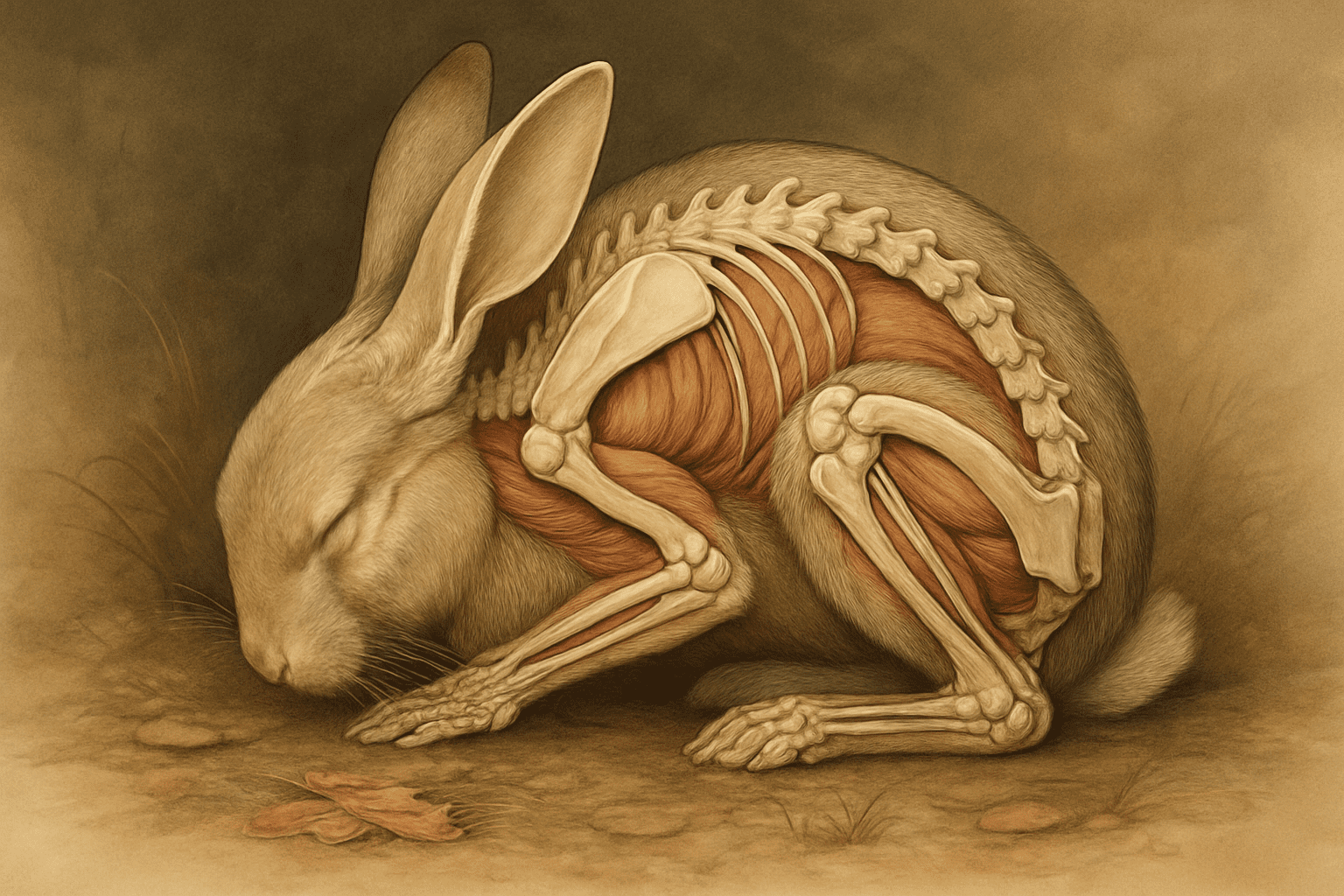

General Structure of the Rabbit Skeleton

The rabbit skeleton is designed for one primary purpose: speed.

In the wild, the ability to accelerate rapidly and change direction suddenly is a matter of survival. To achieve this, evolution has favoured a skeleton that is light, flexible, and minimally reinforced.

Key facts:

- The skeleton makes up only 7–8% of the rabbit’s total body weight, compared to 12–15% in a cat or dog.

- Bone density is low, and the cortical walls (the hard outer layers) are thin.

- Joints are highly mobile, allowing for extraordinary flexibility and agility.

This lightweight construction allows rabbits to outrun predators — but it comes at a cost.

Their bones are far more susceptible to fractures than those of sturdier mammals, and their spines, in particular, are vulnerable to sudden forces.

A rabbit’s skeleton is built for motion, not impact.

Understanding this balance is crucial to preventing life-threatening injuries in domestic settings.

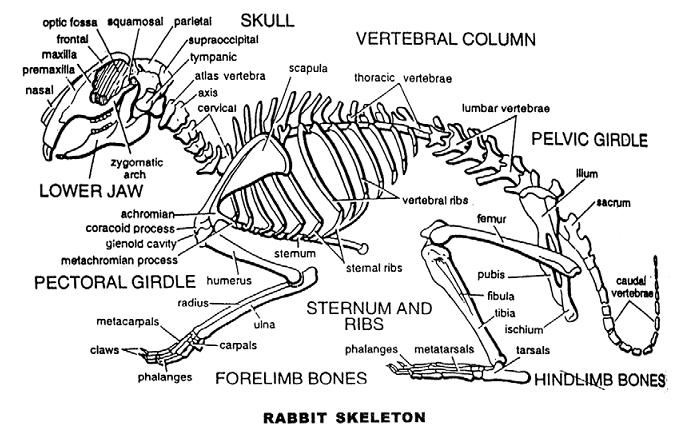

Key Features of the Rabbit Skeleton (Spine)

The rabbit spine is both a strength and a vulnerability.

It provides the flexibility needed for explosive movement, but it is prone to serious injury if subjected to sudden, uneven force.

Spinal breakdown:

- 46 vertebrae in total:

- 7 cervical (neck)

- 12 thoracic (upper back, attached to ribs)

- 7 lumbar (lower back)

- 4 sacral (fused, pelvis area)

- 16 coccygeal (tail)

Critical points to understand:

- The lumbar spine (especially L6 and L7) is the most common site of fracture.

- The vertebral bodies are elongated and the cortical bone is thin, offering little protection against flexion and torsion injuries.

- Sudden kicks, improper restraint, or panic movements can easily generate enough force to fracture the lumbar vertebrae — often causing instantaneous hindlimb paralysis or spinal cord injury.

Even seemingly minor accidents — a rabbit jumping from a height, twisting mid-air, or struggling when picked up — can produce fatal consequences.

The spine is built to bend and flex during movement, not to resist static forces or torsional stress.

When handling rabbits, full spinal support is not optional — it is a matter of basic survival.

Hind Limb and Forelimb Anatomy

The rabbit’s skeletal structure is highly specialised for rapid acceleration and sharp changes in direction.

The hind limbs, in particular, are powerful engines but this strength, if misdirected, can lead to serious skeletal injuries.

Hind limbs:

- Built for propulsion, not endurance.

- The tibia and fibula are long and fine-boned, adapted for sudden thrusts.

- The tarsal bones (equivalent to the human ankle) are small but flexible, allowing strong rear-foot kicks.

- Hindlimb kicks can generate forces sufficient to fracture the rabbit’s own spine if the body is not properly supported.

Forelimbs:

- Lighter and shorter than the hind limbs.

- Designed more for steering and balance than for absorbing impacts.

- The radius and ulna are delicate, and the carpal bones (wrists) are highly flexible but fragile.

- Rabbits have five digits on each front paw and four on each rear paw, each ending in a strong nail for traction and digging.

Key handling risk:

- If a rabbit is allowed to thrash, struggle, or kick while being lifted or restrained without full body support, the mechanical force generated by the hindlimbs can easily outmatch the spine’s structural limits.

A rabbit’s muscles are powerful.

Their bones — and particularly their spinal cord — are not built to survive uncontrolled force.

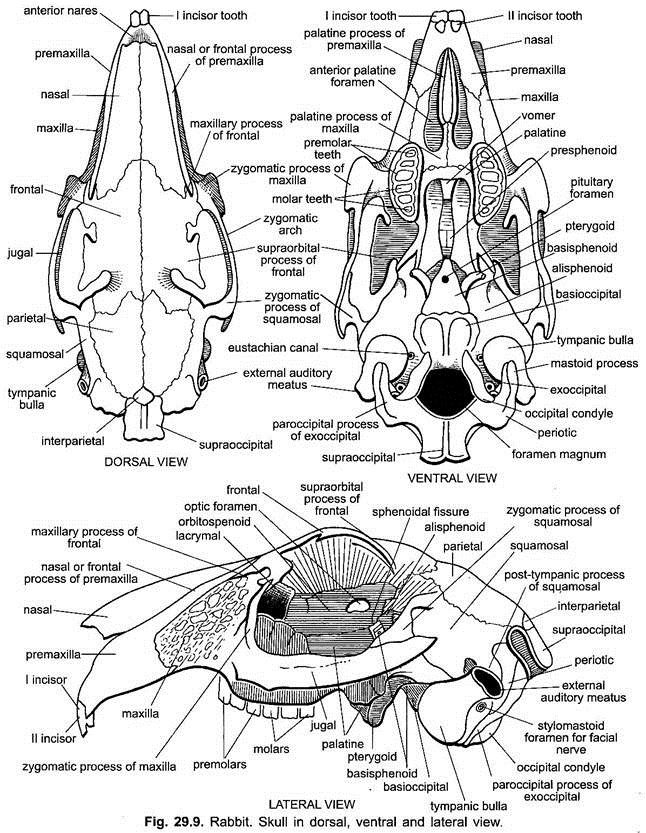

The The Structure of the Rabbit Skeleton (Skull)

The rabbit skull is a highly specialised structure designed for herbivorous grazing, acute sensory perception, and continuous dental growth.

Its lightweight construction allows rabbits to maintain a high field of vision and effective chewing, but it also leaves them vulnerable to trauma and chronic disease.

Key anatomical features:

- The cranial bones are thin and fragile, especially around the orbits (eye sockets), nasal passages, and maxilla (upper jaw).

- The mandible and maxilla form a hinge designed for lateral grinding, not vertical shearing. This movement is essential for processing coarse forage.

- Rabbits possess 28 continuously growing teeth:

- 6 incisors (4 upper, 2 lower)

- 10 premolars

- 12 molars

Critical considerations:

- The incisors and cheek teeth grow throughout life at a rate of 2–3 mm per week.

Constant natural wear is required to prevent malocclusion and root overgrowth. - Root elongation from insufficient wear can lead to:

- Penetration of the thin maxillary bone into the nasal cavity.

- Compression or infection around the lacrimal ducts (tear ducts), causing chronic eye discharge.

- Formation of abscesses in the jaw or orbit, often silent until they become advanced and difficult to treat.

- Orbital bones are so delicate that even minor trauma a fall, a collision, or rough handling — can cause fractures, bleeding, or internal swelling.

- The nasal bones are similarly lightweight, increasing the risk of sinus infections or facial deformities if compromised.

A rabbit’s skull is not built to absorb force.

It is built to enable constant chewing, wide vigilance against predators, and the ability to flee — not to survive impact.

Clinical reality:

- Dental disease is not just a dental problem.

- It is a skull disease that can affect vision, breathing, feeding, and even brain health if neglected.

Understanding the fragility and complexity of the rabbit skull is critical not only for handling safety but for recognising and preventing some of the most serious welfare problems rabbits face in captivity.

Common Rabbit Skeleton Injuries in Rabbits

The rabbit’s skeletal system is built for rapid movement, not for resisting trauma.

In domestic environments, this mismatch between design and circumstance makes certain injuries tragically common.

Most frequent skeletal injuries:

- Spinal fractures:

- Typically occur at the lumbar spine, especially between L6 and L7.

- Often caused by sudden powerful kicks when the rabbit is restrained, improperly lifted, or startled.

- Fractures frequently result in irreversible hindlimb paralysis or spinal cord compression.

- Long bone fractures (legs):

- Tibia and fibula fractures are common from falls, jumps from heights, or becoming trapped in gaps (e.g., between cage bars or furniture).

- Radius and ulna fractures in the forelimbs can occur if rabbits brace awkwardly when falling or landing.

- Pelvic fractures:

- Result from severe trauma such as collisions, dog attacks, or mishandling.

- May cause secondary problems with urination or defecation if pelvic nerves are damaged.

- Mandibular and maxillary trauma (jaw injuries):

- From facial impacts, poor dental health, or chronic infection weakening the bone.

- May lead to feeding difficulties, abscesses, or sinus involvement.

- Orbital injuries:

- Due to the fragility of the eye sockets, blows to the head can easily cause orbital fractures, bleeding behind the eye, or even eye loss.

How injuries happen:

- Improper lifting without full spinal and hindquarter support.

- Allowing rabbits to jump from high surfaces (tables, beds, sofas).

- Rough handling, chasing, or startling.

- Housing environments that allow slips, falls, or entrapment.

- Fighting between rabbits, especially if they kick or bite each other violently.

A rabbit may appear agile and strong

but skeletal injuries are often sudden, catastrophic, and life-threatening.

Prevention is not simply good practice.

It is a duty of care.

Closing Note

The rabbit skeleton is a masterpiece of evolutionary design but also a point of profound vulnerability in the domestic world.

Respecting the fragility of these animals is not about fear.

It is about understanding their nature, protecting their wellbeing, and ensuring they live full, healthy lives without preventable suffering.

At Redbeck, knowledge is not optional.

It is the foundation of every decision we make about the animals entrusted to our care.

Related: How to Handle Rabbits Safely (Based on Skeletal Structure)

References

- Harcourt-Brown, F. (2002). Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- (Covers skeletal anatomy, common injuries, and handling precautions in depth.)

- Meredith, A., & Lord, B. (2014). BSAVA Manual of Rabbit Medicine. British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- (Provides clinical guidance on rabbit musculoskeletal system and trauma management.)

- Jenkins, J. R. (1999). Orthopedic diseases of rabbits. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 2(1), 107–122.

- (Specialised article on rabbit fractures, spinal injuries, and skeletal care.)

- Richardson, V. (2000). Rabbits: Health, Husbandry and Diseases. Blackwell Science.

- (Useful for basic skeletal and anatomical reference, including housing and handling implications.)

- House Rabbit Society (HRS). Guidelines for safe handling and housing. Retrieved from www.rabbit.org

Copyright © Redbeck Rabbit Boarding. This article is free to share with credit. No part may be copied, edited, or republished without permission.