Rabbit Grooming the Redbeck Way

Rabbit Health Checks You Can Do During Grooming

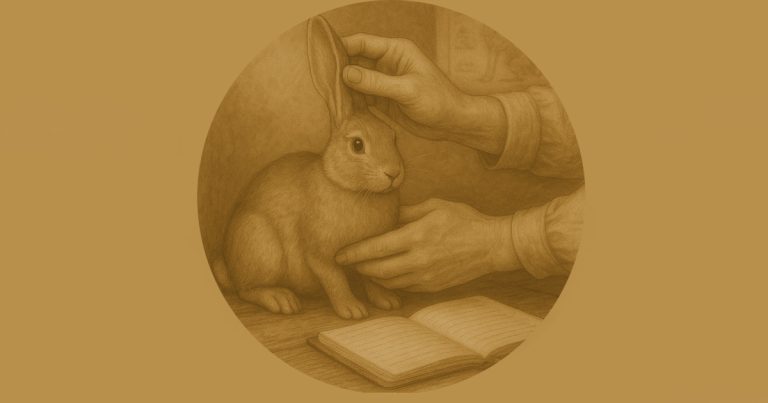

At Redbeck, rabbit grooming isn’t just a routine—it’s a relationship.

Before we touch a comb or trim a nail, we begin with a proper head-to-tail check. This tells us everything we need to know. How the rabbit holds themselves. How they react to being touched. Whether they’re about to relax—or bolt. We’re not just scanning for mats or mites. We’re reading stress, sensitivity, and trust.

From there, we adapt. If the animal’s confident and used to being handled, we crack on. If not—we slow it down. Sometimes, the first few minutes aren’t grooming at all. They’re teaching. Gently combing the surface coat while we hold the rabbit calmly, letting them feel what it means to be touched without fear. It might take two minutes. It might take fifteen. But that’s time well spent.

And here’s the deeper truth: grooming is essential to a rabbit’s psyche. From birth, their mother pins them and cleans them. It’s not optional. It’s part of survival. As they grow, they groom their siblings. Later, they groom their mates. And when they bond with us? Grooming is part of that too. It’s how rabbits connect, communicate, and care.

Skip it, and you’re not just risking knots and GI stasis—you’re cutting off one of the rabbit’s most instinctive social behaviours. That’s why we cringe when people say, “Oh, they don’t like being picked up, so we don’t.” That’s not compassion. That’s avoidance.

Grooming done right is calm, cooperative, and rooted in trust. It’s not about getting the job done. It’s about understanding the job in the first place.

What to Check: A Head-to-Tail Walkthrough

As we go through the initial check, patterns start to reveal themselves—quickly. Whether it’s dense tufts collecting around the back end during a moult, soreness near the genitals, or tension in the feet, the animal shows you where the discomfort is… if you’re watching properly.

You don’t need words. The rabbit’s body tells you everything:

- A flick of the back

- A twist away

- Feet being pulled back sharply

- Or—yes—even a nip

And let’s be honest—rabbits can bite. We’ve all met the ones who do. But in almost every case, the bite isn’t aggression. It’s a message: “That hurts.” “That scares me.” “Too much.”

It’s your job to listen before it gets to that point.

Some of the most common trouble spots:

- Knots and compacted fur near the rear end during moulting

- Dampness, irritation, or build-up around the genitals

- Matted pads or early sore hocks on the feet

These aren’t grooming tasks. They’re welfare warnings. And this check gives you a map for where to proceed carefully, and where to back off entirely.

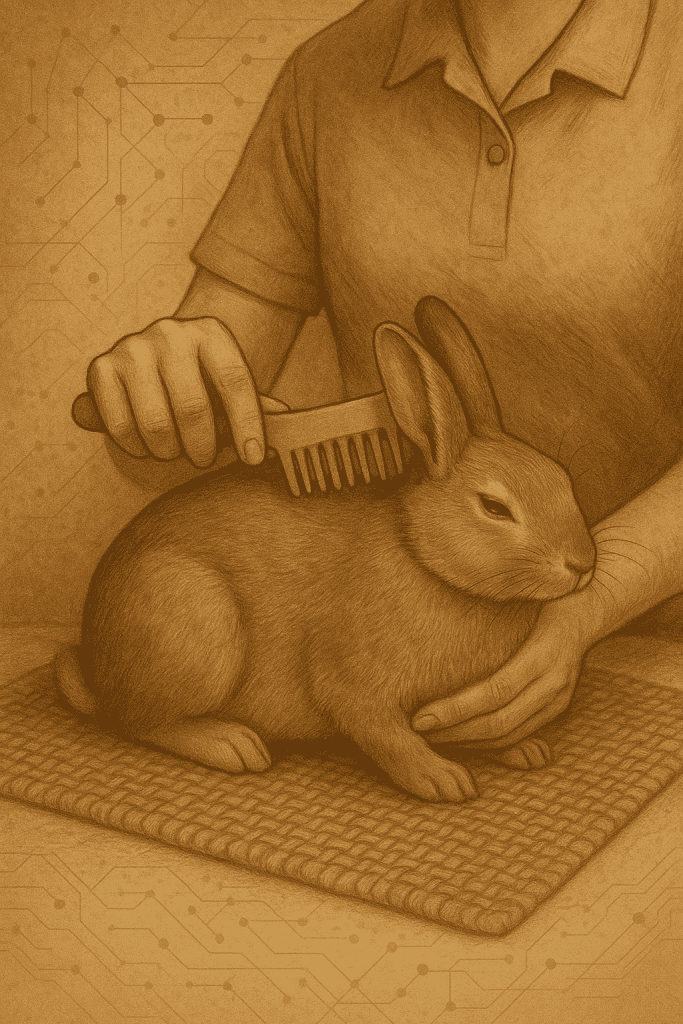

Tools We Actually Use for rabbit grooming (And What We Absolutely Don’t)

There are endless racks of so-called “rabbit-safe” grooming tools out there—metal shredders, wire slickers, fine-toothed torture devices, and enough pink fluff to make you think you’re grooming a Build-A-Bear. We don’t touch any of them.

At Redbeck, our toolkit is simple, calm, and built for trust—not trauma.

What we use most:

- Low-noise clippers – Used in 90% of our grooming work. Not to shave to the skin, but to safely remove dense knots and mats without tugging or tearing. Quiet, efficient, and far less distressing than scissors.

- Snub-nose scissors – For delicate areas where clippers can’t reach. Always with rounded tips—never anything sharp near skin.

- Simple plastic hair comb – Nothing fancy. Just enough to lift fur, work through surface layers, and feel what’s underneath without digging in.

That’s it. No fuss. No gimmicks.

What we don’t use:

- Metal shedding tools (Furminators, slicker brushes, de-shedding rakes) – These rip more than they remove. Especially dangerous on thin-skinned rabbits.

- Fine metal combs – We’re not looking for nits. These do more harm than good, especially in moulting season.

- Anything labelled “self-cleaning” or “pet-friendly” without testing it first – Just because it says it’s for rabbits doesn’t mean a rabbit would agree.

The goal is to reduce stress and discomfort—not look busy with a kit full of sharp things. If your tools make the rabbit twitch, flinch, or bolt—you’ve already lost the room.

Stage One: Feet First – The Real Start to Every Groom

Once we’ve assessed the animal and know how it’s likely to react, we begin with the feet and nails. Always.

Why? Because overgrown nails affect everything—posture, balance, even how the rabbit tolerates being held. If they’re snagging, sore, or compensating, it skews the whole process.

Nail clipping isn’t a one-size-fits-all job. At Redbeck, we use different clippers depending on the animal:

- Human nail clippers – Ideal for small breeds or just taking the sharp tips off young nails.

- Snub-nose curved clippers – For medium-sized rabbits where control matters more than brute strength.

- Sharp dog clippers – For big breeds like Belgian Hares and Continentals, where density and claw shape demand something stronger.

We’ve also developed a technique that speeds things up and keeps us accurate: using your thumbnail as a guide, placed gently against the rabbit’s toe. With your thumb as a reference, you can clip quickly and cleanly without needing to hold a torch in your teeth.

But let’s be honest—sometimes we do hit the quick. It’s rare, and we aim to avoid it, but it happens. Especially when the nails are seriously overgrown. And here’s something people forget: when a rabbit’s nails are too long, the quick grows longer too. So even if you want to tidy them up properly, you’re often forced to choose between:

- Leaving the nail too long, or

- Clipping slightly deeper so that, over time, the quick recedes and the nail can return to a healthy length

It’s not ideal—but we make the call based on what’s in front of us. When that happens, we leave that paw until last, apply a pain-relieving blood-stopping powder, and monitor the animal closely. It’s not about perfection. It’s about outcome and welfare.

And again: this is why grooming is a two-person job. One person focuses on handling. The other handles the tools. The rabbit gets done properly, calmly, and safely.

Stage Two: The Genital Area – Sensitive, Matted, and Often Ignored

Once the feet are done and the animal’s more settled, we move to the next major welfare zone: the genitals.

This is nearly always a problem area. Long-haired rabbits, older rabbits, unhandled rabbits—most come in with matting, scald, or compacted fur here. It’s sore, sensitive, and understandably not their favourite part of the process.

But it has to be done.

Left untouched, this area traps urine, invites infection, and becomes a perfect storm for flystrike. We approach it slowly, carefully, and in stages. If the animal gets too tense or defensive, we don’t push on—we reset. That usually means placing them back with their front feet near the edge of the table and returning to something calm and familiar—grooming the top coat along the shoulders or back to settle them.

Once they’ve dropped their guard again, we return to the job. Round by round, not all at once.

We work to the animal’s tolerance, not our clock.

People often ask us, “How long will it take?”

And we tell them: that’s not our decision to make. It’s the rabbit’s.

If they’re confident, clean, and used to being handled—it’s quick. If they’re fearful, filthy, and knotted into themselves from neglect, it can take hours. Sometimes, hours every day for a week, just to fix what’s been allowed to build up over years.

This isn’t a timed service. It’s a welfare intervention.

The animal leads. We follow.

Stage Three: Bellies and Armpits – The Forgotten Zones

Most people never check a rabbit’s belly or armpits. But if you’ve ever had a knot in your own armpit—or a patch of sore skin under your waistband—you’ll understand just how uncomfortable it can be.

Rabbits don’t lie back and offer their stomach. They’re not cats. And they certainly don’t roll over like a dog for a belly rub. Getting to these areas takes patience, trust, and a second set of steady hands.

But these zones matter. Mats in the armpits restrict movement. Compacted fur on the belly traps dirt and moisture. And once these knots get wet or tangled with hay, they don’t shift on their own.

Technique matters here. We use:

- A simple wide plastic comb to gently lift and tease apart surface mats

- Occasionally snub-nosed scissors—only when the mat is raised and we can clearly see daylight between skin and fur

- For anything deeper, we use low-noise clippers—slow, careful, no dragging

These aren’t areas to rush. The skin here is soft, the limbs are mobile, and a frightened rabbit can twist like a cat when they want out. So we go gently. We keep the sessions short. And if it takes a couple of passes, so be it.

The goal here isn’t speed. It’s comfort. Because if we miss a mat under the arm, we guarantee the rabbit won’t.

Stage Four: Dewlap and Chin – The Sneaky Ones

The dewlap (that big fluffy fold under the chin) and the chin scent glands are some of the most overlooked areas in grooming—but they’re also some of the most problematic if left unchecked.

These spots don’t usually look bad at first glance. The fur’s soft, the rabbit doesn’t complain—until you part the fluff and realise what’s been hiding underneath.

The dewlap collects moisture. From drinking, grooming, even breathing. In females especially, it can get thick and matted fast. Once it compacts, it traps heat and starts to smell. The skin underneath can become irritated, and in extreme cases, break down completely.

The chin scent glands—tiny slits right under the jawline—are where rabbits mark territory. These areas can get waxy and clogged over time, especially in rabbits with thick coats or during hormonal phases.

Here’s how we manage them:

- Gently lift the chin and part the dewlap fur with a plastic comb

- If mats are present, use fingers or a wide comb to tease out gently—clippers only if absolutely necessary

- Check for dampness or smell. If it’s musty or sour, there’s likely build-up

- For chin glands, use a damp cotton pad or Q-tip with warm water to clean excess wax (no digging, just wiping)

Rabbits won’t usually react here—until you’re too rough. The trick is to lift and separate, not push and pull.

Done well, this step goes unnoticed. Done poorly, and you’ve got a rabbit who won’t let you near their face again for weeks.

Stage Five: Head and Ears – Where Trust Is Won (or Lost)

The head and ears might seem like the easy part—but they’re often the most sensitive zones of all. Get it wrong here, and the rabbit will clock it. Next time, they’ll fight you from the start.

That’s why we treat this part like a negotiation, not a task.

The face first.

Rabbits groom their own faces obsessively, but it’s still worth checking. Around the eyes, fur can clump with hay, especially in long-haired breeds or during moulting. A simple wipe with a damp cotton pad usually does the trick. If you spot discharge, crusting, or weeping—it’s a vet job.

The nose should be clean and dry. Snuffles, sneezing, or damp fur around the nostrils aren’t grooming problems—they’re early health warnings.

And yes—this is also where you may be introduced to the sharpness of a rabbit’s teeth.

Sometimes it’s deliberate—a warning nip. More often, it’s just poor aim, frustration, or confusion. Especially with guinea pigs, who like to mouth as a form of “what’s this?” You’re in close quarters. Keep your fingers steady, and don’t assume the head is the safe zone.

Now the ears.

Lops are prone to wax buildup and dampness. Upright ears are usually drier, but not immune. Gently lift the ear and inspect the inside. You’re looking for:

- Waxy build-up

- Strong odours

- Thick debris or dark crusts (which could indicate mites)

We never go digging. Just a gentle wipe around the outer canal with a damp pad is enough. Q-tips only for visible wax at the surface—and never inserted deep.

This is also a good time to check the jawline. Run your fingers gently along the sides. You’re feeling for swelling, heat, or hidden abscesses—especially important in rabbits with known dental history.

What we’ve learned:

- If a rabbit flinches hard when you touch their ears or jaw, it’s worth checking for infection, mites, or pain

- If they lean into it, you’ve probably just become their favourite human

Like everything else at Redbeck, this step isn’t rushed. It’s read. We pay attention to how the animal responds and adapt. That’s not pampering—it’s respect.

Stage Six: The Body and the Moulting Minefield

Once we’ve dealt with feet, sensitive zones, underarms, and ears, it’s time for the bulk of the job: the body coat.

This is where most people think grooming starts. They’re wrong. By the time we get here, we’ve already done the hard stuff. But that doesn’t mean this bit’s easy.

Moulting—not “shedding”—is a rabbit’s natural coat cycle. It comes in waves, lines, and patches, often looking worse after grooming than before. That’s normal. Rabbits aren’t broken. It’s biology.

What matters is how you handle it.

We don’t go in heavy.

We start with our hands—feeling for tufts, thick patches, damp fur, or hidden scabs. Then we work with:

- A soft rubber brush or mitt (gentle but effective for surface fur)

- A plastic comb for deeper coat layers

- Fingers to lift moulting tufts—never tugged, always plucked gently if loose

We do not use:

- Metal slickers

- Rakes

- “De-shedding” tools that look like cheese graters

They might work on dogs. They’ll rip a rabbit’s skin.

How often we do this depends on the rabbit:

- Short-haired rabbits: once a week in normal coat, daily during moults

- Long-haired rabbits: daily. No exceptions

- Elderly, overweight, or disabled rabbits: more often, and more gently. They can’t groom themselves, so we step in

Some rabbits moult in tidy patterns. Others look like a storm in a fur factory. That’s not your fault—and it’s not theirs. Don’t chase perfection. Just reduce the load. Prevent fur ingestion. Spot trouble.

Don’t Forget the Back End – Where It All Collects

Before we wrap up the coat work, there’s one place that needs extra attention: the back end.

In the show world, this is the first place judges look. And for good reason. It’s where deep knots form, undercoat mats settle, and moulting hits hardest. It’s also the area most rabbits struggle to reach themselves—especially larger breeds, overweight rabbits, or those with arthritis.

We approach this slowly, using a simple plastic back-comb and a clear step-by-step method.

Here’s how we do it:

- Gently lift the wealth of fur that sits over the hindquarters—what we call the “moulting undercoat layer”.

- Run your fingers through the fur underneath. If it feels smooth and clean, you’re good. If it clings, sticks, or catches—you’ve got work to do.

- Use the comb to lift from the base outwards. Short, soft strokes. No dragging.

- Loosen the coat gradually, working your way up and out—never towards the tail or against tension.

You’ll be shocked at what comes out. This is where the majority of loose coat tends to hide—quietly thickening the rabbit’s rear, trapping heat, and adding bulk that shouldn’t be there.

Do it right, and you’ll see the difference immediately—not just in condition, but in shape. The hindquarters look lighter, leaner, and properly defined. More importantly, the rabbit feels it. Movement becomes easier, and irritation fades.

This isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Our Favourite Finishing Trick

Once the coat’s been combed through, we finish with a trick we’ve learned over the years—simple, but unbelievably effective:

Wet hands. Just a light dampening, nothing dripping. Then run your hands through the coat—both forwards and backwards. Unlike cats or dogs, rabbits don’t mind fur being moved against the grain, and this technique lifts an astonishing amount of loose hair.

Rub your hands together to collect the fur, flick it into a bin, re-wet, repeat. You’ll be shocked how much fluff this removes—especially the fine undercoat that combs miss. It’s calming for the rabbit, grounding for the handler, and leaves the coat clean, light, and settled without overworking the skin.

You can also use a dry pet foam with this same technique for extra lift and coat condition.

But here’s the caution—we never use scented dry shampoos, especially with bonded pairs.

Rabbits identify each other by smell. Change that scent—even slightly—and you risk confusing or upsetting the bond. We’ve seen full-on fallouts over a bit of lavender-scented grooming spray. If one comes back smelling “wrong,” it can trigger fights, re-bonding issues, or flat-out rejection.

So if we use anything, it’s unscented, minimal, and followed by time together so the scent can naturally rebalance.

Because grooming isn’t just physical. It’s social. And done wrong, it can break more than fur.

When Grooming Becomes a Welfare Emergency

Most grooms are routine. Some are long. But a few… are urgent.

Every so often, we’re faced with a rabbit that’s reached crisis point—where matting, impacted caecotrophs, and urine scalding have created a situation that’s no longer about comfort. It’s about health. And sometimes, survival.

These are rabbits that can no longer pass droppings properly. Ones whose urine has soaked into dense, filthy mats. The result? Raw skin, swelling, infection risk, and pain they can’t tell you about—unless you know how to read it.

This is one of the very few times we will bathe a rabbit.

And even then, it’s not a full-body soak. It’s a targeted, careful clip and back-end clean.

Here’s how we handle it:

- We clip away all matted and contaminated fur around the tail, genitals, and hind legs—never with scissors, only with quiet, low-heat clippers

- We bathe the affected area only—just the back end. Never the full rabbit

- We use a medical-grade manuka honey-based shampoo, which gently cleans, soothes, and helps sanitise without adding scent or sting

- Once clean, we thoroughly dry the area—warm towels, soft airflow, no direct heat. A damp rabbit is a cold rabbit. And cold leads to stasis, shock, and worse

Afterwards, we assess the damage: scalded skin, ulceration, even necrosis in extreme cases. And this is where judgement matters.

Nine times out of ten, we can help.

But that one time? It’s a veterinary emergency.

We have no hesitation in saying it. If the rabbit needs sedation, anti-inflammatories, antibiotics, or pain relief—that’s beyond our skill set. We’ll advise the owner clearly and directly. No fluff. No delay.

Because grooming is care.

But knowing when to step aside? That’s care too.

Final Thoughts: When and How Often?

People often ask us, “How often should I get my rabbit groomed?”

The honest answer? It depends. Every rabbit is different. Breed, coat type, age, lifestyle, and health all play a part.

But here’s a simple rule of thumb:

When the nails start to look too long—it’s probably time for a haircut.

It’s strange when you think about it—humans aren’t all that different.

We let things grow until something feels off, then suddenly we realise: time for a tidy.

So pick up your rabbit regularly. Look. Listen. Feel.

Their coat will tell you what it needs—if you’re paying attention.

And if ever in doubt?

Redbeck can help.

Health Checks Page

Anchor: “…during grooming, we check for early signs of health issues…”

External Links

Article on Flystrike (Vet Help Direct)

Anchor: “flystrike can be fatal”

Link: https://www.vethelpdirect.com/vetblog/2020/06/03/flystrike-in-rabbits/

RWAF (Rabbit Welfare Association & Fund)

Anchor: “flystrike risk” or “welfare issues in rabbits”

Link: https://rabbitwelfare.co.uk

British Rabbit Council

Anchor: “As BRC members…”

Link: https://thebrc.org

House Rabbit Society

Anchor: “moulting and coat cycles” or “grooming advice”

Link: https://rabbit.org/grooming-handling/grooming/

PDSA Rabbit Health Advice

Anchor: “regular rabbit health checks”

Link: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/pet-help-and-advice/looking-after-your-pet/small-pets/rabbits