Rabbit Handling

Intro: Why Rabbit Handling Matters

Rabbit Handling, Rabbits aren’t built like dogs or cats. Their skeletons are light, their reflexes fast, and their instincts hardwired for flight. They’re prey animals to their core—watchful, reactive, and always calculating their nearest exit. That evolutionary design makes them agile, yes—but also astonishingly fragile.

A rabbit can panic in a heartbeat. And when they do, those powerful hind legs can thrash with enough force to fracture their own spine. It’s not drama. It’s biology.

The sad truth is many handling injuries don’t come from neglect—they come from good intentions and a lack of understanding. Picking a rabbit up without proper support, restraining them too tightly, or even catching them off guard can cause real harm. Not all injuries are immediate or visible, either. Subtle trauma, bruising, or skeletal strain can leave lasting effects.

Handling a rabbit safely isn’t just about keeping them calm—it’s about reading their posture, respecting their boundaries, and holding them in a way that supports their frame and nervous system. It’s practical empathy. You’re not just lifting a pet. You’re carrying a body designed for flight, not captivity.

Want to understand the anatomy behind this?

Read our guide to the rabbit skeleton.

Rabbits Are Prey—Start There

Rabbits didn’t evolve to be handled. They evolved to avoid being eaten.

For thousands of years, they’ve been a staple food source for anything fast enough and sharp enough to catch them—foxes, stoats, birds of prey, dogs, cats, even humans. That pressure has hardwired their entire physiology and psychology around one thing: survival by escape.

And that shows up everywhere.

- Their skeleton is light, built for sprinting, not impact.

- Their skin and fur tear easily—it’s a defensive mechanism to break free.

- Their nerves and reflexes are tuned to react, not negotiate.

- Their stress response isn’t like a dog’s—it’s closer to shock.

They don’t vocalise fear. They don’t growl or bark or hiss. They either bolt, freeze, or shut down completely. Which is why so many people mistake a still rabbit for a calm one—when in fact, it’s terrified.

If you pick up a rabbit the wrong way, it might not bite or scream. It’ll just quietly panic—internally—and you won’t know it until the damage is done.

Understanding rabbit handling starts here:

they think like prey—because they are prey. And our job, if we’re going to care for them, is to handle them in a way that doesn’t feel like capture.

What Fear Looks Like in a Rabbit

Fear in a rabbit doesn’t always look dramatic. You won’t get barking or hissing or flailing claws like you would with a cat or dog. Rabbits are prey animals—they don’t advertise fear, they hide it. And if you don’t know what to look for, you’ll miss it.

Here’s what fear actually looks like:

1. Stillness That’s Too Still

A truly relaxed rabbit might loaf, blink slowly, or flop sideways.

A scared rabbit freezes—body tense, ears flat or bolt-upright, nostrils twitching. It’s not calm. It’s calculating.

2. Wide Eyes (Whites Showing)

If you can see the white of the eye, the rabbit is on high alert. That’s a classic sign of panic—not curiosity.

3. Tucked-In Head or Flattened Posture

Sometimes they hide their face in your elbow or press it against the ground. This isn’t affection—it’s self-protection. “If I can’t see the predator, maybe I’m safe.”

4. Rapid Breathing

Fast, shallow breathing. Chest rising and falling quickly. The body is bracing for flight—or collapse.

5. Silent Struggle

A frightened rabbit might try to wriggle, but more often it just submits. Don’t mistake that stillness for comfort. Submission isn’t trust—it’s a last resort.

Why the Vet Immediately Thinks “Spinal Injury”

When a rabbit comes into the clinic with a weak back end—dragging its legs, unsteady, or suddenly lame—the vet’s first thought isn’t stroke, arthritis, or mystery illness.

It’s trauma.

Because 9 times out of 10, that’s what it is. Not intentional abuse—but incorrect handling. Someone lifted the rabbit by the chest and let the back legs dangle. Or it kicked mid-air. Or it wriggled and was held tighter instead of closer.

Even if the injury wasn’t witnessed, the signs are often clear:

- Lameness

- Hind limb weakness

- Reluctance to move

- Pain response in the lower spine

- Acute collapse under stress

That’s why the first thing the vet usually recommends is an X-ray. They’re looking for:

- Vertebral fractures

- Spinal compression

- Pelvic damage

- Or micro-fractures that explain neurological symptoms

And it’s not paranoia. It’s pattern recognition. They’ve seen this story too many times.

❗The Cost of That Mistake

Even if the X-ray comes back clear, you’re still left with:

- A rabbit in pain

- A huge vet bill

- A lot of guilt

- And a rabbit that now panics every time you reach for it

Which is why this conversation matters. Not to guilt-trip—but to prevent a repeat.

It’s not about wrapping rabbits in bubble wrap.

It’s about respecting what they are: fast, fragile, flight-wired animals that break more easily than they show.

Rabbits Hate Being Picked Up—And That’s Normal (At First)

Here’s the bit no one puts on the pet shop leaflet: rabbits don’t like being picked up.

Not at first. Not naturally. Not instinctively.

And not because you’re doing it wrong—but because to a rabbit, being lifted equals being caught.

You’re triggering millions of years of survival instinct. Hawks don’t ask permission. Foxes don’t wait until the rabbit’s ready. So when your hands come in from above, the rabbit’s brain doesn’t go “cuddle time”—it goes “I’m about to die.”

It doesn’t matter how gentle you are. Or how quiet the room is. Or whether you used to have one that “loved being picked up” (it probably didn’t—it just froze and gave up).

This isn’t disobedience. It’s evolutionary defence.

Think of It Like Vertigo—But for Survival

Some describe it as a kind of vertigo—and while that’s not quite right biologically, it’s accurate enough emotionally.

When you lift a rabbit, you’re taking away its footing, removing every escape route, and placing it entirely at your mercy. It’s not the height—it’s the helplessness.

Imagine being picked up ten feet in the air by something five times your size. No control, no footing, no guarantee of safety. That’s how it feels to a rabbit—unless you handle them the right way.

Fear Is Normal—But It’s Meant to Be Replace

This fear is natural. But it’s not permanent.

Handled correctly, calmly, and early, rabbits learn that being picked up isn’t a prelude to panic—it’s a manageable, even neutral, experience.

Handled regularly—but safely—they build trust.

Handled rarely—and badly—they become unhandleable.

You’re not removing the instinct. You’re retraining the response.

This is why we pick up rabbits from the start. Not constantly. Not to cuddle. But to show them that being lifted isn’t dangerous. That they’ll be supported, held close, and put back down again without incident. That it’s routine—not trauma.

Welfare Isn’t Hands-Off

You’ll often hear: “Don’t pick them up unless absolutely necessary.”

That advice is well-meaning—but dangerously incomplete.

Because in real life, rabbits need to be handled:

- You must check for flystrike daily in summer

- You must administer medication, inspect wounds, trim nails

- You must vaccinate

- And sometimes, you need to intervene fast

If your rabbit panics at every touch, or bolts every time you lift it, that’s not protection. It’s a welfare risk in waiting.

Welfare isn’t about avoiding handling—it’s about doing it properly.

A Domestic Rabbit Can Live 12 Years or More

Wild rabbits are lucky to see their second birthday.

Domestic rabbits—if cared for properly—can live well beyond twelve.

But that doesn’t happen on good intentions alone.

You can’t check a rabbit’s health from across the room.

You can’t spot problems through a playpen fence.

And you can’t give treatment to a rabbit that’s never learned to accept your hands.

If we’re going to give them safety, we also have to give them preparedness.

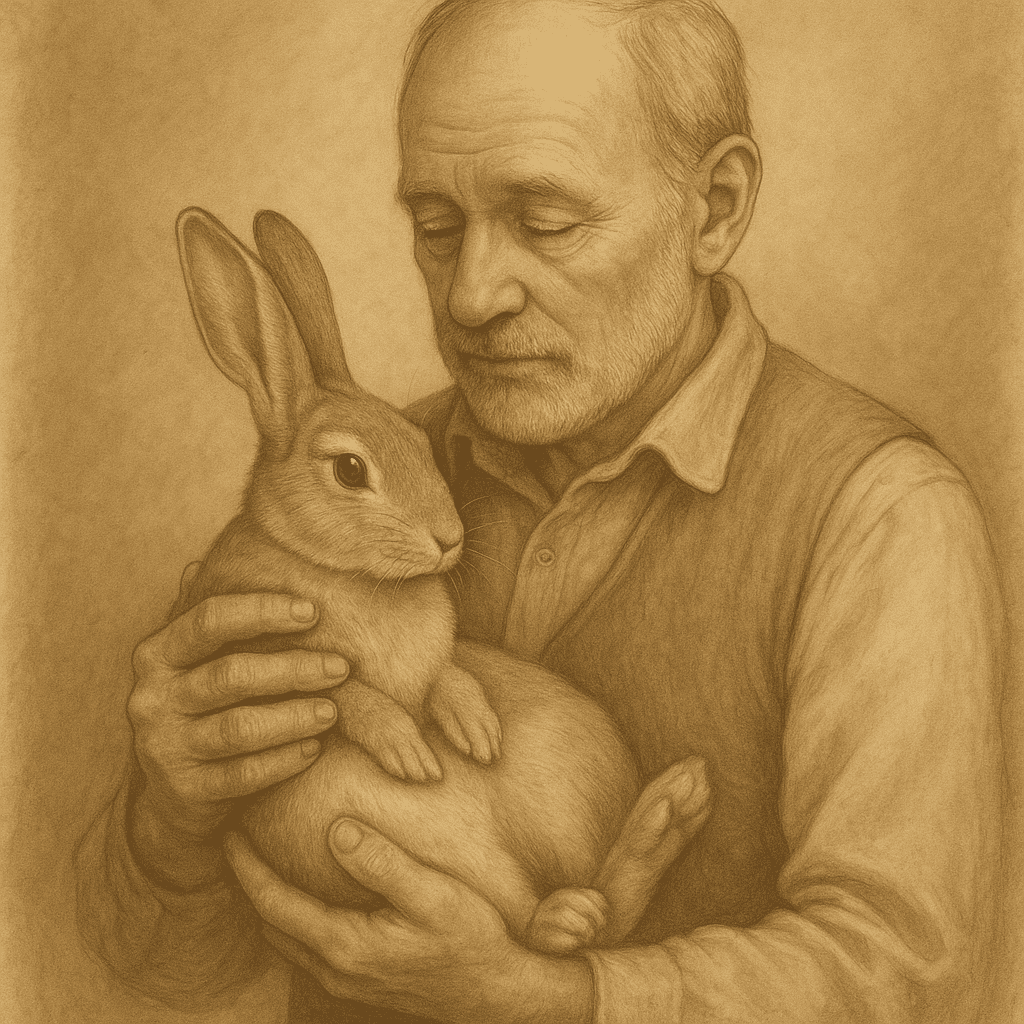

✅ Train the Rabbit You Want to Care For

- Pick them up regularly—but briefly

- Support both ends—chest and bum

- Keep them close to your body

- Let them hide their head if they need to

- And wait until they stop struggling—then put them down

Over time, they learn: “I’m safe. I’m not being hunted. I’m not being hurt.”

And that’s the rabbit you can care for when it matters most.

about you.

Common Rabbit Skeleton Injuries in Rabbits

How injuries happen:

Related: How to Handle Rabbits Safely (Based on Skeletal Structure)

References

- Harcourt-Brown, F. (2002). Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- (Covers skeletal anatomy, common injuries, and handling precautions in depth.)

- Meredith, A., & Lord, B. (2014). BSAVA Manual of Rabbit Medicine. British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- (Provides clinical guidance on rabbit musculoskeletal system and trauma management.)

- Jenkins, J. R. (1999). Orthopedic diseases of rabbits. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 2(1), 107–122.

- (Specialised article on rabbit fractures, spinal injuries, and skeletal care.)

- Richardson, V. (2000). Rabbits: Health, Husbandry and Diseases. Blackwell Science.

- (Useful for basic skeletal and anatomical reference, including housing and handling implications.)

- House Rabbit Society (HRS). Guidelines for safe handling and housing. Retrieved from www.rabbit.org

Copyright © Redbeck Rabbit Boarding. This article is free to share with credit. No part may be copied, edited, or republished without permission.