Gastrointestinal Tract Function in Rabbits

Rabbits are strict herbivores. Their relatively small body size makes it difficult to store large volumes of coarse fiber as might be done in a cow or horse. The GI tract attempts to eliminate fiber as quickly as possible. Large indigestible fiber particles stimulate healthy motility of the GIT. The rabbit GI tract then breaks down the digestible portion of the food to produce the needed nutrients, some of which are absorbed directly from the GI tract and some of which are eaten again in the form of cecotropes.

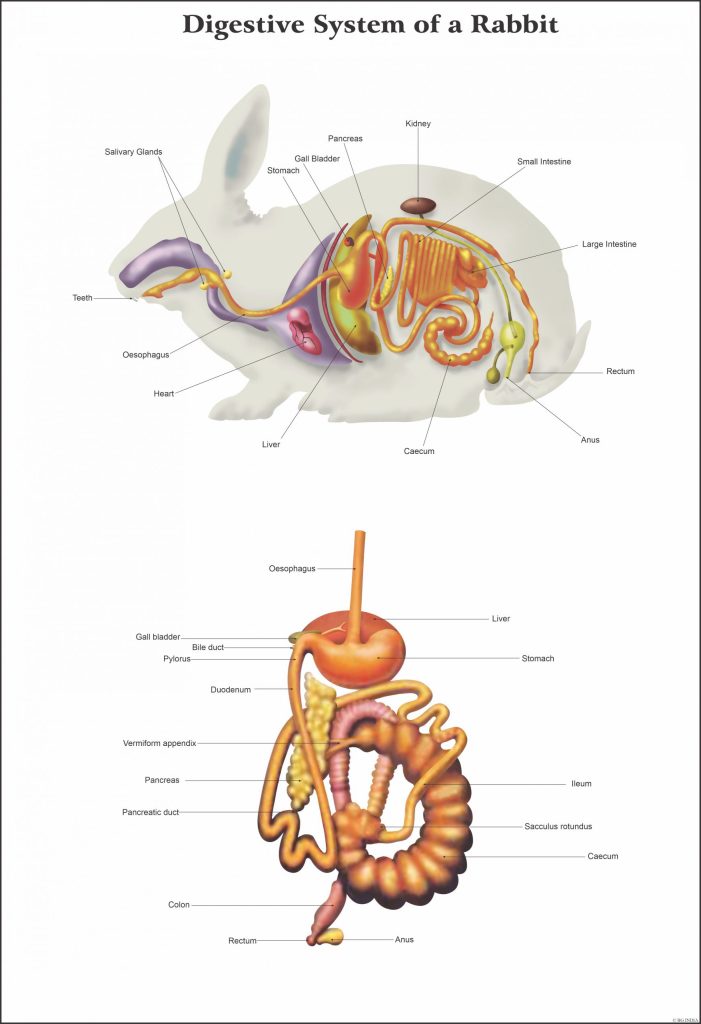

Food in the stomach is essentially sterilized, massaged a bit and broken down into smaller particles. It then moves into and through the small intestine where nutrients are extracted, and more water is added resulting in a fluid content. At the point where the small intestine flows into the large intestine, it is connected to a large blind sac called the cecum.

In the cecum resides a specific population of bacteria, yeasts and other microorganisms that break down the digestible portion of the gut content. Through bacterial fermentation, amino acids, fatty acids and certain vitamins are produced. Any changes in the delicate balance of the flora of the cecum can have disastrous results for the rabbit. Factors that can interfere with the function of the cecum include a diet too high in carbohydrates and/or too low in indigestible fiber; toxins; some medications (especially some antibiotics); dehydration; extreme stress and other systemic disease (such as liver or kidney disease). Some of the nutrients produced in the cecum are absorbed directly thorough the wall of the cecum, but most are contained in cecotropes, which are nutrient-rich “feces” that are passed from the cecum, through the large intestine to the outside. Rabbits know when these cecotropes are being excreted and eat them directly from the anus. Cecotropes are produced approximately 4 to 8 hours after a meal. When the cecotropes are digested, the nutrients are extracted and absorbed by the rabbit. Occasionally cecotropes are not eaten and can be seen in the toilet area. Cecotropes are irregularly shaped, greenish in color, coated with mucous and have a strong odor.

Waste feces are the hard, round, dry droppings found in the toilet area. These feces have a high fiber and low moisture content and do not contain any nutrients for the rabbit. Waste feces are produced during the first 4 hours after a meal.

Appropriate amounts of liquid are important in the rabbit diet to promote proper mixing and sorting of the ingesta (intestinal contents) in the lower intestine and cecum. If a rabbit becomes dehydrated these contents become dry and impacted.

How Gastric Stasis Occurs

The most common cause for gastric stasis is an inappropriate diet. As we can see from this brief discussion of the GI tract a healthy diet for a rabbit includes large amounts of both digestible and indigestible fiber, has a low to moderate carbohydrate level and contains adequate moisture. A diet consisting primarily of grass hay and green leafy foods works well. A diet of highly concentrated carbohydrates and low indigestible fat levels can promote abnormal GI motility. Overfeeding of high energy commercial rabbit pellets, commercial rabbit treats and high carbohydrate foods such as grains and legumes are examples of dietary items that are too high in carbohydrates and too low in indigestible fiber. When rabbits are fed these foods, the result is a slower than normal GI motility.

Although diet is the most common cause of gastric stasis, any condition that changes GI tract motility can result in this disease. This would include chronic high levels of stress in the environment, postsurgical adhesions, ingestion of toxins or other foreign material, chronic dehydration (lack of access to clean water), painful conditions and dental disease (these conditions change eating habits), and other systemic disease that causes alterations in GI tract motility such as liver or kidney disease.

As the movement of material through the GI tract slows, the ingesta sits longer then normal at any point, particularly in the stomach and in the cecum. Fluid continues to be extracted from this ingesta while it is delayed and eventually the ingesta can become thick and dry as it dehydrates. The dehydrated ingesta causes further slowdown of GI motility causing a vicious cycle. The result is dry, impacted material in the stomach as well as the cecum, which ceases to move altogether. The rabbit stops eating and drinking because nothing is moving and further aggravates the condition. Now we have a “ball” of material in the stomach that can be felt on a physical examination and seen on an x-ray. Dehydrated stomach contents viewed on an x-ray exhibit a halo of air demonstrating that there is little liquid present.

So where does the hair come from? Rabbits always have some hair in their stomach contents. They groom themselves constantly and swallow the hair. A true “hairball” is comprised of nearly 100% hair as in cats or ferrets. In rabbits, hair is mixed with stomach contents in a loose mass. As the stomach contents dehydrate as described above, the largest particles are left behind, which includes the hair. The liquid stomach contents gradually turn into a solid tightly adhered mass. If you look closely at a “hairball” you can see that it is made up of both hair and dried stomach contents. In a few rare instances, the longhaired breeds of rabbits, such as Angoras and Jersey Wooly’s, can develop excessive amounts of hair in the stomach because the hair is abnormally long. Humans have created this situation through the alteration of our pet’s genetics. In these species it is beneficial to brush the pet frequently to reduce the amount of hair eaten.

To sum it up, the cause of this condition is not hair in the stomach, but rather a GI tract motility disorder that results in dehydrated ingesta in the stomach and the cecum. If the underlying problem is not corrected, the condition is destined to reoccur.

Signs of Gastric Stasis

The following is a list of signs that are commonly noted with gastric or cecal stasis:

- Rabbits will eat less over a period of days or weeks.

- Eventually rabbits completely stop eating

- The waste droppings become smaller, then completely stop

- Often affected rabbits will be bright and alert for several days after they stop eating.

- Rabbits will refuse to eat pellets but will chew the paper on the bottom of the cage, the woodwork or wall board, all of which are sources of the fiber they are craving.

- Some rabbits have periodic soft, pudding-like stools prior to a complete loss of appetite.

- As the condition progresses with further dehydration of GI contents and finally complete shutdown of the GI tract, the rabbit becomes increasingly lethargic, depressed and ultimately can die.

If your rabbit exhibits ANY of these signs, contact your veterinarian right away. It is important to note that with gastric stasis, the changes usually come on gradually. If complete intestinal obstruction occurs with dried ingesta or any other material, the signs appear rapidly and are much more dramatic, requiring immediate veterinary attention. The signs of ingestion of a toxic substance may be similar.

Signs of intestinal obstruction or toxicosis:

- Rabbit suddenly stops eating

- Depressed or lethargic, may be reluctant to move or appear bloated

- Suddenly stops producing any stools

- Rabbit may make grunting noises or continually grind the teeth in response to abdominal pain

- Eventually the pet will go into shock and collapse.

If you see any of these signs in your rabbit you should consider it a dire emergency and seek veterinary assistance immediately.